Wednesday, July 31, 2024

POETRY SPOT

----------oOo----------

Margaret Elizabeth Sangster (1838 – 1912) was an American poet, author, and editor. Her poetry was inspired by family and church themes, and included hymns and sacred texts. She worked in several fields including book reviewing, story writing, and verse making. For a quarter of a century, Sangster was known by the public as a writer, beginning as a writer of verse, and combining later the practical work of a critic and journalist. Much of her writing did not include her name.

From:

The below poem. The Sin of Omission, explores the notion of regret and the consequences of neglecting small acts of kindness. It emphasises that it is not the actions taken but those left undone that can haunt us. The poem's focus on missed opportunities and neglected responsibilities aligns with the Victorian era's preoccupation with morality and social duty. Compared to Sangster's other works, it shares a similar theme of regret and the importance of empathy, but with a more concise and direct approach. The poem's simple and accessible language makes its message universal and relatable across time periods.

The Sin Of Omission

By Margaret E. Sangster

It isn't the thing you do, dear,

It's the thing you leave undone

That gives you a bit of a heartache

At the setting of the sun.

The tender word forgotten;

The letter you did not write;

The flowers you did not send, dear,

Are your haunting ghosts at night.

The stone you might have lifted

Out of a brother's way;

The bit of hearthstone counsel

You were hurried too much to say;

The loving touch of the hand, dear,

The gentle, winning tone

Which you had no time nor thought for

With troubles enough of your own.

Those little acts of kindness

So easily out of mind,

Those chances to be angels

Which we poor mortals find—

They come in night and silence,

Each sad, reproachful wraith,

When hope is faint and flagging

And a chill has fallen on faith.

For life is all too short, dear,

And sorrow is all too great,

To suffer our slow compassion

That tarries until too late;

And it isn't the thing you do, dear,

It's the thing you leave undone

Which gives you a bit of a heartache

At the setting of the sun.

----------oOo----------

Tuesday, July 30, 2024

FACTS

----------oOo----------

Bilbo Baggins journeyed many places in Middle-Earth, but his quest extends to other planets, too. The Lord of the Rings was published in 1954, adding to the story that J.R.R. Tolkien began with The Hobbit in 1937.

All of the mountains on Saturn’s moon Titan are named after peaks andcentral characters in The Lord of the Rings series: Bilbo, Handir, Nimloth, Arwen and Faramir Colles were all named in 2012. (“Colles” isn’t another Tolkien reference: it’s actually a term that planetary experts use to refer to hills.) Naming a hill after Gandalf wasn’t approved until July 2015, a full 360 years after Titan was discovered in 1655.

__________

Adolf Hitler, JRR Tolkien, and Anne Frank's father all fought in the Battle of the Somme. Ralph Vaughan Williams and Siegfried Sassoon also fought in one of the world's bloodiest battles.

The Battle of the Somme, also known as the Somme offensive, was a major battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and the French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place between 1 July and 18 November 1916 on both sides of the upper reaches of the river Somme in France. The battle was intended to hasten a victory for the Allies. More than three million men fought in the battle, of whom more than one million were either wounded or killed, making it one of the deadliest battles in all of human history. Debate continues over the necessity, significance, and effect of the battle.

Hitler was injured fighting for the German Empire on the Somme. Over the years there has been speculation that he suffered a wound to his genitals as well as the leg wound suffered while serving with a Bavarian unit, which gave rise to the legend that he only had one testicle.

Adolf Hitler c 1914

Ralph Vaughan Williams was a composer whose work The Lark Ascending is frequently voted Britain's most popular piece of classical music. He enlisted as a private in the Royal Army Medical Corps on New Year's Eve, 1914, the same year he produced the work.

Otto Frank, Anne Frank's father, was the only member of the family to survive the Holocaust. Born in Frankfurt he was drafted into the German Army in 1915 served on the Western Front for the rest of the war, earning promotion to Lieutenant. He moved the family from Germany to Amsterdam in 1933 after Hitler's rise to power and increasing violence and discrimination against Jews, even those who had put their lives on the line for their country.

Harold Macmillan, the British Conservative Prime Minister from 1957 to 1963, was an officer in the Grenadier Guards who was wounded twice during the Somme. He spent the rest of the war recovering and was left permanently affected.

JRR Tolkien, The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings author, was an officer in the 11th Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers. Serving in the difficult northern sector of the Somme battlefield, Tolkien's health eventually suffered. He contracted trench fever at the end of October 1916 and was then sent back to hospital in Birmingham. He was unfit for service for the rest of the war.

Siegfried Sassoon: As a second lieutenant with the 1st Battalion, Royal Welsh Fusiliers, war poet Sassoon witnessed the carnage of July 1 weeks after earning a Military Cross in a daring operation to rescue a soldier in No Man's Land.

Siegfried Sassoon

__________

"Hitler Has Only Got One Ball", sometimes known as "The River Kwai March", is a World War II British song, the lyrics of which, sung to the tune of the World War I-era "Colonel Bogey March", impugn the masculinity of Nazi leaders by alleging they had missing, deformed, or undersized testicles.

Multiple variant lyrics exist, but the most common version refers to rumours that Adolf Hitler had monorchism ("one ball"), and accuses Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler of microorchidism ("two but very small") and Joseph Goebbels of anorchia ("no balls at all").

Hitler has only got one ball,

Göring has two but very small,

Himmler is rather sim'lar,

But poor old Goebbels has no balls at all.

__________

The fruits and vegetables we buy in the grocery store are actually still alive, and it matters to them what time of day it is.

Researchers have discovered that the way we store our produce could have real consequences for its nutritional value and for our health. "Vegetables and fruits don't die the moment they are harvested," according to lead rresearcher Dr. Janet Braam, Professor of Biochemistry and Cell Biology at Rice University in Houston, Texas. "They respond to their environment for days, and we found we could use light to coax them to make more cancer-fighting antioxidants at certain times of day." Even after harvest, they can respond to light signals and consequently change their biology in ways that may affect health value and insect resistance. The researchers made the initial discovery in studies of cabbage. They then went on to show similar responses in lettuce, spinach, zucchini, sweet potatoes, carrots and blueberries.

__________

Splenda is the best-selling artificial sweetener in America.

It was first created by Shashikant Phadnis, a young Indian chemist at Queen Elizabeth College, in London, and his adviser, Leslie Hough, as an insecticide by adding a sugar solution to sulfuryl chloride, a highly toxic chemical. In the violent reaction that followed, a wholly new compound was born: tetra-deoxygalactosucrose.

In 1975, Phadnis was told to test the powder, but he misunderstood; he thought that he heard it as needing to taste it. Uing a small spatula, he put a little of it on the tip of his tongue. It was sweet --- achingly sweet. “When I reported my findings to Les, he asked if I was crazy, “ Phadnis remembers. “ How could I taste compounds without knowing anything about their toxicity?” Before long, though, Hough was so delighted with the substance that he dubbed it Serendipitose and tried putting some in his coffee. “Oh forget it, “ he said, when Phadnis reminded him that it might be toxic. “We’ll survive!”

It turned out to be useless as an insecticide but effective as an artificial sweetener, about six hundred times as sweet as sugar. When mixed with fillers and sold in bright-yellow sachets, it’s known as Splenda, the best-selling artificial sweetener in America.

----------oOo----------

Sunday, July 28, 2024

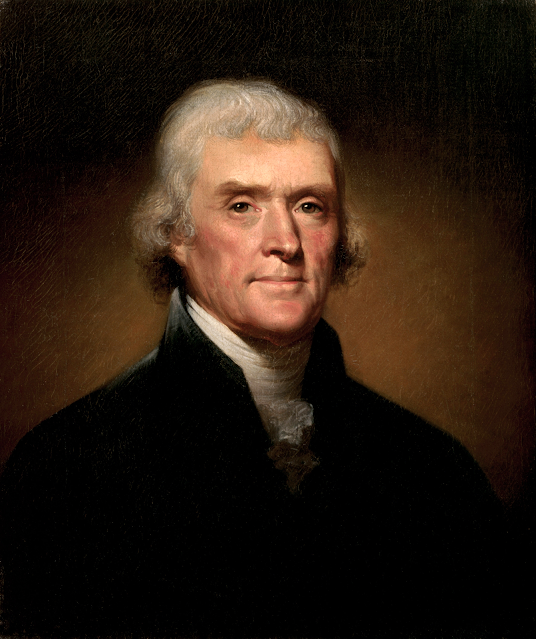

THIMAS JEFFERSON'S 10 RULES OF LIFE

-----------ooOoo-----------

Thomas Jefferson, the third American president, was a great one for giving advice, often to advise family and friends on all-around "best practices."

Jeferson’s axioms were both of his own invention and from classical or literary sources.

Here is a "decalogue of canons for observation in practical life" that the former president imparted in 1825. The list was more popularly known as:

Thomas Jefferson's 10 Rules Of Life

These are Thomas Jefferson’s ten rules for a good life:

1. Never put off till tomorrow what you can do today.

2. Never trouble another for what you can do yourself.

3. Never spend your money before you have it.

4. Never buy what you do not want because it is cheap: it will never be dear to you.

5. Pride costs us more than hunger, thirst, and cold.

6. Never repent of having eaten too little.

7. Nothing is troublesome that we do willingly.

8. Don’t let the evils that have never happened cost you pain.

9. Always take things by their smooth handle.

10. When angry, count to ten before you speak; if very angry, count to 100.

-----------ooOoo-----------

Throughout the 19th century, "Jefferson's 10 Rules" were printed and reprinted in newspapers and magazines. All across the country, the rules were recited and debated and taken to heart.

Inspired by Jefferson's commandments, a twisted list of rules appeared in the Chicago Daily Tribune on Nov. 11, 1878. Numbered and rearranged for clarity, here are

Ten Rules for Young Men

1. Never pay to-day the man you can put off until tomorrow.

2. Never trouble yourself to do for another man what he can do just as well for himself.

3. Never spend your own money when you can get things for nothing.

4. Never buy what you don't want, simply because the man says he is just out of it.

5. Remember that it costs more to go to a high-priced theatre than it does to take a back pew in a free church.

6. Do not despise a 20 cent cigar or a $1 dinner because another man pays for it.

7. Nothing is troublesome to you that other people do for you willingly.

8. Do not poultice your own elbow for the boil on another man's neck.

9. Always pick up a hot poker by the cold end.

10.When angry, be sure you can handle your man before you call him a liar.

Saturday, July 27, 2024

PHOTOS FROM THE PAST

-----------ooOoo-----------

Next in the series of hometowns of overseas Byters and regular contributors, Tim B, who hails from Fayetteville, Georgia USA

-----------ooOoo-----------

About Fayettevile:

From Wikipedia:

Fayetteville is a city in and the county seat of Fayette County, Georgia, United States.

(Tim, you will need to advise the relationship between Fayettville in Georgia and in North Carolina.)

As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 18,957.

Fayetteville is located 22 miles (35 km) south of downtown Atlanta.

Fayetteville was founded in 1822 as the seat of the newly formed Fayette County, organized by European Americans from territory ceded by force the Creek people under a treaty with the United States during the early period of Indian removal from the Southeast. Both city and county were named in honor of the Revolutionary War hero the French Marquis de Lafayette.

Fayetteville was incorporated as a town in 1823 and as a city in 1902.

The area was developed for cotton plantations, with labor provided by enslaved African Americans, who for more than a century comprised the majority of the county's population. Fayetteville became the trading town for the agricultural area.

In the first half of the 20th century, as agriculture became more mechanized, many African-American workers left the area in the Great Migration to northern and midwestern industrial cities, which had more jobs and offered less oppressive social conditions.

A reverse migration has brought new residents to the South, and the city of Fayetteville has grown markedly since 1980, as has the county.

-----------ooOoo-----------

Gallery:

__________

Picture of the proposed Liberty Point statue. On March 24, 1903, an auxiliary to the Liberty Point monument was formed to help raise funds for the erection of a statue on the corner of Person and Bow streets at Liberty Point. Beneath this proposed statue of a lady would be the words "Liberty." Although several money-raising schemes were used, including the sale of this hand-colored postcard, with the statue drawn in, enough funds for the monument could not be raised. The old Opera House, also known as The New Market, is seen on the extreme left.

__________

The Toonerville Trolley that was one of the three trolley cars in Fayetteville from 1906 through 1916. Residents could ride this street car from the top of Haymont Hill down Hay Street and out Gillespie Street to the Massey Hill area for only five cents.

__________

Young ladies ride in a parade that ended in front of Highsmith Hospital on Green Street in Fayetteville in 1911.

__________

The Lyric Theatre was located across from S.H. Kress & Co. on Hay Street in the early 1920s. It was owned by a man who offered free tickets to children who collected tin cans to clean up the city of Fayetteville.

__________

Postcard of the fourth Cumberland County courthouse on the north west corner of Gillespie and Russell Streets in the early 1900s. When the courthouse was built, a part of Russell Street was called Mumford Street.

__________

In March 1914 Fayetteville residents crowded into the old Cape Fear Association grandstand on Gillespie Street where they saw eighteen-year-old George Herman Ruth, who was the youngest player on the Baltimore Orioles team, hit his first home run in professional baseball. It was in this park that he was referred to as "Babe in the Woods” and later “Babe Ruth."

__________

The third Cumberland County courthouse. The first Cumberland County courthouse was a log building constructed at Choeffington near Linden, North Carolina. The second courthouse was built at Campbellton. A later courthouse was erected on James Square [later called Saint James Square] at the intersection of Green, Rowan, Ramsey, and Grove streets. This brick building, which faced south looking down Green Street toward the Market [State] House, was constructed circa 1790 and was demolished in the 1890s. The Confederate Monument was later erected on its site.

__________

Eleanor Roosevelt who, with her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt, visited Fayetteville and Fort Bragg in the late 1930s. The picture was made at the A.C.L. Railroad Depot on Hay Street.

__________

The first street-car in Fayettevile, 1906

__________

The "Florida" yacht at Breece's Landing on the Cape Fear River. The "Florida" was owned by the late Oscar P. Breece, and it ran on the river from the 1940s through the 1960s. A World War II Submarine Chaser was used as a foating dock for the ship. The remains of the Submarine Chaser can still be seen near the old Breece's Landing. The "Florida" is on the right of this photograph near the Submarine Chaser

__________

1920s view of the third LaFayette Hotel that had an impressive tower on the fourth floor. Note the street car lines on unpaved Hay Street in front of the hotel. This is the hotel Babe Ruth stayed in when he hit his first home run in professional baseball in the old ball park on Gillespie Street in March 1914. Apparently Babe loved to ride the hand-operated elevator in that hotel.

__________

Hopefully this means something for Tim . . .

1923 aerial photograph of downtown Fayetteville, no First Citizen Bank building on the corner of Hay and Green Streets; The Bevill's stable occupied the site of the old stone Cumberland County courthouse; the Lafayette Hotel on Hay Street had a tower above the third floor; the old Opera House was still standing on Person Street; Highsmith Hospital (later to become the Millbrook Hotel) can be seen on Green Street; the McNeill Milling Company (the site of Newberry's mill) is still visible on the corner of Old and Green Streets; Central School was on Burgess Street behind the Hay Street Methodist Church; Rogers and Breece Funeral Home was still in the old Martin House Hotel building on Bow street; the City Hall (now known as Fascinate U Children's museum) had not been constructed; the Catholic church was on Bow Street where the Central Fire Department was later constructed; Champion Automotive Equipment Company (owned and operated by Weeks Parker, Sr.) was on the corner of Bow street and Cool Spring Lane near Liberty Point; and the old Eagle Hotel; the Fayetteville Observer and the Public Works office and switch house were across from the Highsmith Hospital on Green Street.

__________

Another view of the third LaFayette Hotel on Hay Street, where Babe Ruth stayed when he hit his first home run in professional baseball.

__________

Hay Street as it looked in the 1960s.

__________

Market Square with The Market House.

From the mid 1800s and until the early 1900s, farmers throughout Cumberland and surrounding counties brought their wagons loaded with cotton and fire wood to the Market House where they were weighed on public scales and then sold to the public.

__________

Hay Street, 1960s

__________

The Fayetteville Stagecoach that carried passengers and mail from Wilmington and Raleigh during the mid to late 1800s. The first "stage house" where the offices of the stagecoach company were kept, was in the Fayetteville Hotel which was built about 1849 on Green Street in the vicinity of St. John's Episcopal Church rectory.

__________

A view of Hay Street as it was in the 1960s. On the left is a huge pencil in front of the OSI Office Supply Company.On the right is the S. H. Kress 5 & 10 cent store where popcorn and candy were sold for 5 cents a bag.

__________

Early 1900s view of a Decoration Day [now called Memorial Day] celebration on Person Street. The New Market and Opera House can be seen on the right in this picture.

__________

In August, 1955 WFLB TV, channel 18, became Fayetteville's first television station. This ultra-high frequency station was one of the first of its kind in North Carolina. The studios and transmitter were located at the present site of radio station WAZZ at 1332 Bragg Boulevard. This pioneering UHF station carriedÊ three networks, ABC, CBS, and NBC. Because of competition from the VHF stations, WFLB TV went off the air in 1959.

__________

Fayetteville High School Majorettes as they appeared in 1952

__________

Fayetteville High School Band members get ready to perform on the football field behind Fayetteville High School on Robeson Street. 1950s

__________

In 1900, Major Benjamin R. Huske founded Huske Hardware House at 405 Hay Street. For more than seventy years, Huske Hardware House did a thriving business serving the people of Fayetteville with the very finest in general hardware supplies. When Benjamin R. Huske was a boy, he joined the Fayetteville Independent Light Infantry and later became commander of that company. Major Huske and his F.I.L.I. company were made a part of the Second North Carolina Regiment during the Spanish American war.

__________

Fayetteville residents stand in front of the old Eagle Hotel (Overbaugh House) as they eagerly await a Fourth of July celebration on Green Street near the Market House. Note the Roman numerals and the Market House clock faces on the wheels of the automobiles.

__________

The Carpentry Force pose for the photographer at the Cape Fear and Yadkin Railway yard in 1889.

__________

Fayetteville policemen and Fort Bragg military, early 1920s. Note the horseshoe over the entrance to the police and fire department headquarters.

__________

In the 1920s the Courthouse Filling Station and Tire Company on the corner of Gillespie and Russell streets was one of the most popular service stations in Fayetteville. As soon as a customer pulled his car into this Esso station, he received immediate service from three attendants who quickly pumped the gas, filled the radiator, checked the oil, the battery and the tires and then cleaned the windshield. The price of gas was as low as 14 cents a gallon.

__________

The Market House as seen from a rescue boat on Person Street during the 1945 flood in Fayetteville, North Carolina

__________

In April 1983, a statue of Marquis de Lafayette was dedicated by citizens of Fayetteville, in impressive ceremonies in Cross Creek Park. The stature is a work of Ference Varga of France who is shown in his studio as he works on another of his many statures. The Lafayette statue is seen on the left. This statue was presented to the city of Fayetteville by the Lafayette Society, which raised all of the funds required to pay for the statue

__________

World-famous aviator, Amelia Earhart [wearing flight coveralls] during her aerial visit to Fayetteville in 1935 at the airport located on the Raleigh Road near the present site of the Veteran's Hospital. The plane she piloted was called an Autogire which was the forerunner of the Helicopter which was invented a year later in 1936. On an attempted flight around the world, the noted flyer and her navigator were lost somewhere near Howland Island in the Pacific in July 1937.

__________

1928 photo of the first Coca Cola bottling plant, located at 225 Mumford Street [now Russell Street] in Fayetteville. Their phone number was 89. The wagon in this picture had a 21 case capacity.

Friday, July 26, 2024

SOUTH AFRICA'S FIRST INTERRACIAL MARRIAGE

___________________

This is lengthier than I originally intended. As I was preparing iiit, like Topsy it 'just growed'.

_______________

Apartheid:

Apartheid, meaning "separateness", “aparthood', was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was characterised by an authoritarian political culture based on baasskap ('boss-hood'), which ensured that South Africa was dominated politically, socially, and economically by the nation's minority white population. White citizens had the highest status, with them being followed by Indians, Coloureds and then Black Africans.

The first apartheid law was the Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act, 1949, followed closely by the Immorality Amendment Act of 1950, which made it illegal for most South African citizens to marry or pursue sexual relationships across racial lines. The Population Registration Act, 1950 classified all South Africans into one of four racial groups based on appearance, known ancestry, socioeconomic status, and cultural lifestyle: "Black", "White", "Coloured", and "Indian", the last two of which included several sub-classifications. Places of residence were determined by racial classification. Between 1960 and 1983, 3.5 million black Africans were removed from their homes and forced into segregated neighbourhoods as a result of apartheid legislation, in some of the largest mass evictions in modern history. Most of these targeted removals were intended to restrict the black population to ten designated "tribal homelands", also known as bantustans, four of which became nominally independent states. The government announced that relocated persons would lose their South African citizenship as they were absorbed into the bantustans.

Apartheid sparked significant international and domestic opposition. During the 1970s and 1980s, internal resistance to apartheid became increasingly militant, prompting brutal crackdowns by the National Party ruling government and protracted sectarian violence that left thousands dead or in detention.The Truth and Reconciliation Commission found that there were 21,000 deaths from political violence, with 7,000 deaths between 1948 and 1989, and 14,000 deaths and 22,000 injuries in the transition period between 1990 and 1994. Some reforms of the apartheid system were undertaken, including allowing for Indian and Coloured political representation in parliament, but these measures failed to appease most activist groups.

Between 1987 and 1993, the National Party entered into bilateral negotiations with the African National Congress (ANC), the leading anti-apartheid political movement, for ending segregation and introducing majority rule. In 1990, prominent ANC figures such as Nelson Mandela were released from prison. Apartheid legislation was repealed on 17 June 1991, leading to multiracial elections in April 1994.

In South Africa in June 1985, the ban on marriage between people of different ethnic backgrounds was finally lifted. The laws were repealed by the Immorality and Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Amendment Act, which allowed interracial marriages and relationships.

_______________

Suzanne Le Clerc and Protas Madlala:

A white who married across the colour line took on the legal status of the darker spouse. That meant living in an area segregated for blacks, Indians or people of mixed race known as “coloureds.”

American Suzanne Le Clerc and South African Protas Madlala (pictured below) were the first couple to tie the knot under the new rules.

However, while whites and nonwhites could marry, the rules of apartheid still dictated where they lived and worked. For Suzanne Le Clerc and her husband Protas it meant they either lived together in a squalid black township or lived apart. Unable to get permission to work in South Africa, Le Clerc took a job in Transkei, a nominally independent black homeland in South Africa, 235 miles from her husband. He lived in a church-run settlement near Durban, where he had a job as a community worker. Tired of being gawked at by curious blacks and sometimes hostile whites, Madlala and his wife avoided shopping or eating out together during their reunions once a month.

For two years, they saw each other once a month, meeting at a friend’s farm halfway between their homes. When Suzanne became pregnant with their first child, they were determined to live together, asking around until they found a white woman who agreed to let them stay in hiding in an apartment on her property. With two children who had been involved in the fight against apartheid—a daughter jailed for sending photographs to the press, and a son exiled for organising trade unions on the docks of the city of Durban—she was willing to take a risk for the young couple.

The baby was a boy, named Darius. After his birth, the Department of Home Affairs required the infant be classified as black, white, Indian, or “coloured,” a term that referred primarily to South Africans of mixed Asian, indigenous, or European descent. Suzanne and Protas refused, adamant that accepting race classification meant accepting the systematic degradation that came with it. “For his race, I wrote ‘human’ on the form,” says Suzanne. The designation was changed afterward by the Department of Home Affairs to “undetermined.”

She remembers her early days of motherhood with some sadness: “I wanted to be a new mother doing new mother things, pushing the baby around in the pram.” Instead, she bundled Darius in blankets to hide his dark skin, sneaking him onto the bus when she occasionally went into the all-white town. “People would look me up and down and gossip,” says Suzanne. “Some recognised me from television. ‘Aren’t you the woman we saw?’ I would say no. Or I would speak French.”

At five years old, Darius was killed by a hit-and-run driver in front of their home. Suzanne does not know if it was an accident or deliberate, related to the black chickens that had been tossed into their yard, the pervading sense they were being watched, retaliation for Protas’s outspoken activism. “The U.S. Embassy looked into it,” says Suzanne, but they were unable to find any conclusive evidence.

Apartheid ended in 1994, but the pressures on Suzanne and Protas—social, political, professional—did not. In 2001, they separated. Adding to tensions, Suzanne had become increasingly worried for the safety of their daughters, four in all: Alicia was born in 1989, then Racquel, Darienne, and the youngest, Saroya. As a chief research specialist and professor of anthropology at the University of Kwa-Zulu-Natal in Durban, where her work focused heavily on how gender roles and culture were connected to the spread of HIV and AIDS, Suzanne feared the country’s growing climate of sexual violence. “When you have a bigger struggle, all other struggles take a back seat,” says Suzanne. “Once apartheid ended, other issues came to the foreground—gender inequality, violence, criminality—issues that there had been no space for when all energies were focused on fighting against segregation.” She and Protas questioned whether South Africa, reeling from tensions caused by sudden political change, was the right environment for their young girls. “Alicia would dress as a boy to walk to school because she couldn’t stand the harassment,” Suzanne says. “As a young woman, I had enjoyed exploring and riding my bike freely through the neighborhood—I wanted my daughters to know how that freedom felt.”

Left to right, Darienne, Saroya, Alicia, and Racquel on the day of Saroya’s graduation from high school.

In 2009, Suzanne and the girls moved to D.C., where she is now a senior anthropologist for the Global Health Bureau at the U.S. Agency for International Development, addressing the socio-cultural and economic determinants of health. Protas stayed in South Africa, where he is a noted political analyst.

Her work still brings her to South Africa, where she remains an external examiner for the University of Kwa-Zulu-Natal. It is a small world: One of her colleagues turned out to be the exiled son of the woman who had rented the apartment to Suzanne and Protas when they left the black township. “I knew about his whole life,” says Suzanne. His name is David. They are now married.

Suzanne visits a Zulu craft shop on her first day in South Africa.

Above left, news clippings from the family scrapbook show Suzanne and Protas at the church and crowds of onlookers at the history-making wedding; at right, Suzanne visits a Zulu craft shop on her first day in South Africa.

On the morning of the wedding, Protas Madlala and Suzanne Leclerc ’78 rode to the church together. It was customary for a bride and groom to arrive separately, but caution prevailed. Although there had been talk of the South African government relaxing its laws, and an official from the U.S. Embassy had agreed to attend the wedding in case of trouble, as they turned down the passage through the sugar cane fields—a deserted road of blind turns and steep, grass-covered hills, the most likely spot for an ambush—the Zulu groom and his white, American bride were afraid.

But the ambush that awaited was not the one they expected. When they reached the church, they found hundreds of onlookers lining the streets, many cheering and crowding the wedding car. Some had followed gossip overheard hours away in Johannesburg; one news photographer was on a rooftop, angling for a shot of the mixed-race couple about to defy the government and marry.

Leclerc, in a handmade gown she had sewn in secret while staying with nuns in a nearby guesthouse, was struck by a song that rose from the crowd: Africa will be saved. “It wasn’t exactly ‘Here comes the bride,’” she reflects.

At the altar, the couple learned their wedding night would not be spent in prison—the apartheid ban on interracial marriage had been lifted just the night before, in tacit acknowledgement of the couple’s wedding plans. Suzanne and Protas would read about it on the front page of the next morning’s newspapers, alongside the photo that accompanied headlines around the world: On Sunday, June 15, 1985, they were South Africa’s first legally-married interracial couple.

As a child in Cumberland, Rhode Island, Suzanne had been an adventurer. She spent hours playing pilgrim or building huts in the woods, soaking up stories her father, an appliance business owner and World War II veteran, told her about life on a submarine in the South Pacific. “I knew that someday I wanted to travel,” says Suzanne. “Not just for the sake of it, but to do something while I was there.”

After graduating high school early, she left home to study health sciences at a community college in Connecticut, then transferred to the University of Rhode Island to major in anthropology. On the second or third day of classes, she sat in a classroom at Chafee Hall and listened as Professor James Loy vocalized the pant hoot of a chimpanzee. “I was so impressed,” says Suzanne. Not long after earning her degree, she announced to her parents that she was joining the Peace Corps. Her mother was initially perplexed—first the anthropology degree (“She didn’t see jobs in the paper for anthropologists,” says Suzanne), now the Peace Corps, which didn’t seem suitable for a young woman—but ultimately supportive. “My dad was very proud,” Suzanne says. “He thought it was wonderful.”

For two years, Suzanne taught English at a lycee in Gabon, on the west coast of central Africa. When it was time to return to Rhode Island, Peace Corps administrators asked her to stay in Gabon for a third year to build a school. There were no other women in the construction program, but having spent part of the previous year working with local doctors to collect ethnographic data researching how people managed illness in their families, she was eager for the opportunity to immerse herself further in the local community. Armed with an instruction manual on how to mix cement and pour a foundation, she hired a crew of nine Gabonese men, making sure to include the native Baka pygmies, whom she had observed as marginalized by the villagers. “Everybody has their prejudices,” she says.

She thinks of returning to Gabon, to see if the school she built still stands. She says, “It’s on my bucket list.”

In graduate school, she met Protas. She had returned to the U.S. to study medical anthropology at George Washington University in D.C.; Protas was a student at American University, earning his master’s in international relations and communications. They met through a mutual friend who was living in the basement apartment of the house Suzanne had rented with other students. Passionate, political—their similarities were striking for a couple that would go on to shock so many with their perceived differences.

Her parents found common ground with their daughter’s boyfriend as well. Suzanne’s father and Protas talked war, politics, history. “The first time I brought Protas home, my father had a big stack of Time magazines for him to read and discuss,” she says. He passed away before he saw Suzanne marry, but she knew she had his blessing. “He liked Protas very much,” says Suzanne.

The couple had planned to settle in the States, but when Suzanne asked Protas to take her home to South Africa to meet his family before the wedding, plans changed. “He was very involved in the movement against apartheid,” says Suzanne. “Everywhere we went, people kept saying, ‘We need him here.’ I felt guilty taking him away.”

By then, Suzanne’s mother was unfazed when she called home to say they had decided to remain in South Africa to marry. Her mother made the journey to South Africa two months later for the wedding—her first time overseas. “At the wedding, Protas’s family presented her with a big bowl of cow’s blood as an offering of thanks,” says Suzanne. “She took it in stride. When reporters asked what she thought of the wedding, she said, ‘Protas is a nice Catholic boy.’ To her, that was the most important thing.”

After the wedding, law did not permit Protas to live outside the black townships. Though interracial sexual relations and cohabitation bans had been repealed, the Group Areas Act—restricting races to live in designated areas—remained. Suzanne was assigned her husband’s legal status (“honorary black,” she says), and the newlyweds lived in a tin-roofed shack in Mariannhill with no electricity or running water, typical conditions in many of the townships that were left to deteriorate by the government in hopes of driving nonwhites out of urban areas to designated rural homelands. While the villagers embraced the couple (“They were so welcoming and supportive, but they were embarrassed that Protas and I were university graduates living in these conditions”), the streets turned violent at night. “The army would come down the main road, patrolling with their guns,” says Suzanne. Suspected informers were necklaced—a rubber tire shoved down over their shoulders and set on fire—or their houses were burned. Unable to obtain a work permit or take the black bus to reach town (her legal status only applied to her residence), Suzanne was isolated. Even so, she still finds things to miss about their life on the homestead. “It was a simple life,” she says. “My sister-in-law would wash her clothes outside in the bucket, and I would wash mine next to her, and we would talk. Neighbors would come around. We would make tea on the kerosene stove, eat avocado sandwiches. In many ways, it was a quiet, simple time.”

By the end of the first year, Suzanne moved out of the township to the city then called Umtata (now Mthatha) in the territory of Transkei, one of the designated homelands nearly 250 miles away from Mariannhill, where she had obtained a work permit to teach at the local university. Protas, whose work as a community organizer was heavily tied to Mariannhill, stayed behind. For the next two years, they saw each other once a month, meeting at a friend’s farm halfway between their homes. When Suzanne became pregnant with their first child, they were determined to live together, asking around until they found a white woman who agreed to let them stay in hiding in an apartment on her property. With two children who had been involved in the fight against apartheid—a daughter jailed for sending photographs to the press, and a son exiled for organizing trade unions on the docks of the city of Durban—she was willing to take a risk for the young couple.

According to Suzanne, “It clamps your personality, living in segregation. You don’t feel that you belong in the public space, you don’t feel free. The apartheid system was so successful at keeping those worlds separate, you had these white grannies going on about their lives, talking about their granddaughters taking ballet. They had no idea of the conditions that blacks were living in beyond their suburbs.”

She adds: “I felt angry at the government, angry at the people. You couldn’t blame them for wanting to enjoy the sunshine and get on with their lives, but they should have wanted to know about their country and the great injustice going on in their backyard. You can’t just live your nice life—with laser security around the house and killer dogs at the gates. Can you enjoy your life like that?”

The daughters, each in their own way, have followed in their parents’ paths. Darienne left this past October for the Peace Corps. Saroya, an international development major, spent her last semester abroad in Central America. Alicia recently earned her master’s in school counseling, and Racquel works in communications for the National Multifamily Housing Council. “Our parents taught us that it was okay to challenge the status quo,” says Alicia. “The things they did together represent making a big, positive change in the world. We are all trying, in the careers we pursue, to make a difference.”

The girls used to go back to South Africa to visit their father, and they visit Suzanne’s family in Rhode Island each year, struck by the two worlds. “When I go to Cumberland, I am always amazed that she met our father and chose to help him with the struggle,” says Alicia. She has imagined the life of her mother: a young woman working in construction with the Peace Corps, a newlywed living in squalor, a first-time mother hiding her newborn baby on the bus. Scrutiny, harassment—even now, fighting for global health—all starting from a childhood in a small town that seems to have changed little since Suzanne was an adventurous girl, riding her bike and hanging on to her father’s stories.

“I am amazed,” Alicia repeats. “She could have lived an easy life.”

Protas Madlala went on to become a respected anti-apartheid activist and political analyst. He started his career as a journalist at ‘The Mercury’ in Durban in the 1980s and later studied in the US where he obtained a degree in International Communication, as well as later being awarded an honorary Doctorate. Madlala died in 2023 aged 68.

Professor Leclerc-Madlala is now an anthropologist whose research and publications since 1995 have focused on the intersections of culture, sexuality, gender and HIV in Africa, especially in South Africa and in relation to young women’s vulnerability. Her academic work as former Professor and Head of the Anthropology Department at the University of KwaZulu-Natal was complimented by active involvement in the design, implementation and evaluation of HIV programs in South Africa and its neighboring countries. She is currently working as a Senior Advisor for HIV and health with the US Agency for International Development.

Prof Leclerc-Madlala has worked as a consultant to UNAIDS, SADC, the World Bank, and WHO, as well as to several regional non-government organizations and community-based organizations. She helped to draft South Africa’s Sexual Offences Act and the Children’s Bill and authored UNAIDS’ 2009 Action Brief on Inter-generational and Transactional sex in Southern Africa. She worked with the Commission on Gender Equality, the South African Law Commission and other legal bodies to assess various cultural and medical practices for human rights violations. Professor Leclerc-Madlala is also a member of the Scientific Committee of the International AIDS Society, the American Anthropological Association, and the Southern African Association of Anthropologists.

___________________

Gallery:

Apartheid, 1967

Sign in Durban that states the beach is for whites only under section 37 of the Durban beach by-laws. The languages are English, Afrikaans and Zulu, the language of the black population group in the Durban area.

A sign in Johannesburg