-----------ooOoo-----------

The US word ‘badass’ can mean different things in different contexts: brave, tough, mean, cool and so on.

Perhaps we can stay with the comment about the rhinoceros: hard to describe but you know one when you see one.

Here is a bio about a true badass . . .

-----------ooOoo-----------

Chaplain Robert Preston Taylor

Chaplain (Major General) Robert Preston Taylor, USAF (1909 – 1997) was an American military officer who served as the 3rd Chief of Chaplains of the United States Air Force.

-----------ooOoo-----------

Why he was a badass:

Taylor enlisted as a chaplain in the US army in September 1940, his unit being located in Manila in the Philippines. With the declaration of war and invasion by the Japanese, the Philippine Division was transferred to the front lines on the Peninsula of Bataan. Chaplain

Bataan:

The Battle of Bataan (January 7 – April 9, 1942) was fought by the United States and the Philippine Commonwealth against Imperial Japan, the most intense phase of the Japanese invasion of the Philippines during World War II. Under General Douglas MacArthur, he Bataan Peninsula and the island of Corregidor were the only remaining Allied strongholds in the region.

During the Battle of Bataan, America’s first major loss in the Pacific theatre of World War II, Taylor supported the U.S. combatants as they endured disease, starvation, supply issues, and traumatic devastating bombardment. Seemingly abandoned by their country that didn’t get them the supplies or reinforcements they needed, American defenders in Bataan were beset by malaria and other tropical illnesses and subsisted on whatever food they could get their hands on — scraps of rice, monkey, meat, dogs, rats, and slugs. Meanwhile every morning ushered in a fresh barrage from the attacking Japanese. There, during the months long battle, Taylor won a Silver Star for rushing into open fire to evacuate wounded men.

The American surrender at Bataan to the Japanese after three months of fighting, with 76,000 soldiers surrendering in the Philippines altogether, was the largest in American and Filipino military histories and was the largest United States surrender since the American Civil War's Battle of Harpers Ferry.

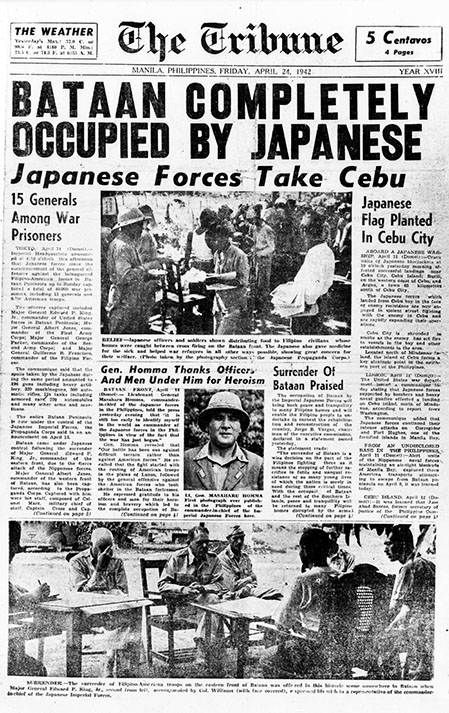

The invading Japanese controlled the Philippine media, which portrayed imperial forces as helpful liberators. This front page from the Manila Tribune claimed that Japanese occupation will bring peace and tranquility to the Philippines, April 24, 1942.

U.S. soldiers and sailors surrendering to Japanese forces at Corregidor, May 1942. Captured Japanese photograph

Bataan Death March:

The Bataan Death March, the forcible transfer by the Imperial Japanese Army of 75,000 American and Filipino prisoners of war, began on 9 April 1942. The total distance marched to various camps was 65 miles (105 km). Sources report widely differing prisoner of war casualties on the march: from 5,000 to 18,000 Filipino deaths and 500 to 650 American deaths during the march.

The march was characterised by severe physical abuse and wanton killings. POWs who fell or were caught on the ground were shot. After the war, the Japanese commander, General Masaharu Homma and two of his officers, Major General Yoshitaka Kawane and Colonel Kurataro Hirano, were tried by United States military commissions for war crimes and sentenced to death on charges of failing to prevent their subordinates from committing atrocities. Homma was executed in 1946, while Kawane and Hirano were executed in 1949.

A photograph of a burial detail at Camp O'Donnell, the terminus of the "Death March".

Prisoners of war on the Bataan Death March.

Prisoners of war on the Bataan Death March.

POW:

Taylor survived the march and was interred, along with tens of thousands of other POWs in the notorious Cabanatuan prison camp in the Philippines. The Japanese imperial army wasn’t known for its compassionate treatment of POWs, but what Taylor endured in the camp far superseded that of most of its detainees.

As a chaplain, Taylor considered it his duty to support his fellow soldiers both spiritually and physically. To accomplish this, he communicated with a network of spies both within and without of Cabanatuan’s fences, including the Filipino resistance. Together, they worked to smuggle food, medicine, and messages from family into the camp, and military intelligence out of the camp.

When the Japanese discovered the spy network, they were furious. They cracked down on all the chaplains in Cabanatuan, torturing many of them to death. Taylor was thrown into solitary confinement in the “heat box.” This was a tiny bamboo cage, with very narrow slats, that was too small to stand, lie down, or stretch out his legs. The Japanese placed the box under the direct heat of the sun and kept him there for nine weeks straight. There, Taylor read the Bible five times and also worked through Dostoevsky’s “The House of the Dead.”

After weeks in the box, Taylor was no longer moving or responsive. American prison doctors lobbied the Japanese for the right to remove Taylors body and bury him and were given permission. The doctors pulled out the limp and lifeless body and quickly realised that Taylor was actually breathing faintly. They secretly snuck him to what passed for an “infirmary” in the camp. After weeks in the infirmary, he was hobbling around the camp on crutches. He had made a miraculous recovery and he used his condition to inspire hope in his fellow soldiers.

When a crowd of prisoners gathered around him, he told them, “Ask me about my condition. I’m dirty, nasty, and all I have on is my underwear. Can you smell the stench of my rotting teeth? Listen to me, listen without pity, I’m not going to die. I’m going to live and you are too, because God is going to give us strength.”

Former prisoner of war Benjamin Steele's drawing of one prisoner giving a drink to another at the Cabanatuan camp.

Hell Ships:

Unfortunately for him, his miraculously recovery came at the worst time possible. It was late 1944 and the Japanese were starting to lose the war and were panicking. Soon, America would retake the Philippines. The Japanese started making plans for moving the healthy prisoners who could still work, transporting them to the Japanese mainland and out of reach of American hands. The sick, infirm, and injured prisoners remained behind and those who survived would later be rescued in a daring American raid on the camp.

However the healthy prisoners were shipped to Japan. To transport their human cargo, the Japanese threw thousands of POWs at a time on the so-called “hell ships.”

The term refers to a ship with extremely inhumane living conditions or with a reputation for cruelty among the crew. It now generally refers to the ships used by the Imperial Japanese Navy and Imperial Japanese Army to transport Allied prisoners of war and rōmusha (Asian forced slave laborers) out of the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies, Hong Kong, and Singapore in World War II. These POWs were taken to the Japanese Islands, Formosa, Manchukuo, Korea, the Moluccas, Sumatra, Burma, or Siam to be used as forced labor.

The Japanese military packed thousands of POWs into dark, suffocating conditions in ships’ holds. Men would panic, suffocating to death or turning on each other in their hysteria.

In a tragically ironic twist, American bombers often strafed these Japanese ships, sending the soldiers trapped in the hold to the bottom of the ocean.

Taylor graduated from the infirmary just in time to be forced aboard the Oryoku Maru along with 1,600 others.

Inside the hold, “The heat was indescribable, unbearable,” Taylor remembers. During the first dark night aboard the ship it was pitch black and some men were delirious from fear and thirst, literally biting the people next to them and sucking on their blood. “The worst nights of our lives,” Taylor claimed.

The next morning, American bombers found the ship and bombed it, crippling it irreparably. Taylor and 1,300 others survived the explosion and swum to the shore, where the Japanese kept them outdoors, exposed to the roasting sun, and on starvation rations for a week. Those who were badly injured in the explosion were beheaded by the Japanese. The rest were packed into the hold of yet another ship, where they were fed only rarely during the three week long voyage to Japan.

While moored at the harbor in Japan, this ship was also discovered by American planes and strafed again, killing even more. Of the original 1,600 who made the journey, only a few hundred had survived, Taylor among them, but he had suffered a broken arm during the ship bombardments.

Liberation:

The group was transported around prisoner camps in Japan, where they were treated relatively well due to their weakened and injured state. They were fed poorly, but the rations were better than they had been in the Philippines and they were given light work to do. After a few months, they were liberated from the camps. Taylor weighed only 98 pounds. He was also the only chaplain to survive Japanese imprisonment.

After the war:

After surviving the Bataan Death March and forty-two months of captivity as a prisoner of war, Taylor returned home in 1945 to find that his wife, Ione, who had been told that he had not survived, had remarried just one month earlier.

In 1950, Taylor married Mildred Good.

He stayed in the military, reached the rank of major general, and was named Air Force Chief of Chaplains by President John F. Kennedy. Taylor retired to Texas in 1963, where he served as a lecturer and preacher at the Southwest Baptist Theological Seminary.

His decorations and awards include the Silver Star, Bronze Star and the Presidential Unit Citation with two oak leaf clusters.

Gallery:

Interview with Chaplain Taylor (lengthy and detailed):

From the above interview:

Chaplain Taylor:

Of course, there were rough times, but never once did I give up, you know, did I succumb to these temptations. A man could literally die if he wanted. If he just gave up, he could die. I've seen them die who just gave up, and they'd be dead in five minutes—just turn over and die. It was easy to do. But you have to keep your chin up and you have to look forward to live through such circumstances.This was not because I was any better than anybody else or those of us who survived were any better. I think the key to all of it, though, was . . . of course, the providence of God, but in his good way we were able to be optimistic and to keep on fighting, keep on pushing, keep on pulling, not only for yourself but for those about you. That's the key to it. I don't think I could have ever made it if I'd just been pulling to see that Preston Taylor got through. That's not the point at all.It brings up the big question about what's life all about. It's not just for me or just for you. If we try to live it in that way for our own gratification, our own benefit, then we soon give up. If you get to thinking about, "Now, gee, there's no use me fighting this thing because I am not going to make it." But if you think there is a reason to fight because it might help somebody else to make it, you see, that's the key. I think that's a key to life, really.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.