---------oOo---------

The Americans celebrate the Fourth of July in a big way, the following article is both illuminating and interesting about the event and the date.

It is from the National Geographic at:

---------oOo---------

America declared independence on July 2—so why is the 4th a holiday?

The colonies had already voted for freedom from British rule, but debates over slavery held up the formal adoption of the Declaration of Independence.

Byerin Blakemore

July 3, 2020

Fireworks, flags, and hot dogs: The Fourth of July is steeped in patriotism and tradition, and celebrated as the day disgruntled American colonists broke ties with Great Britain and declared their intention to found a democratic nation of their own.

But the history behind the holiday isn’t so clear-cut. The anniversary of American independence is July 2, not July 4. And the revolutionaries who founded the nation didn’t guarantee all of its residents “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

In 1774, after years of unfair taxation and imperial control, complaints against the British crown had reached a fever pitch in the 13 American colonies. War had begun to look inevitable and so, in September, delegates from the colonies met to discuss their grievances in what they called the Continental Congress.

The process of declaring independence didn’t get underway until June 7, 1776, when Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee introduced a resolution in the Second Continental Congress. Just 80 words long, the Lee Resolution proposed the dissolution of any political connection between Great Britain and the colonies. Although most delegates supported independence, the proposal was not guaranteed to pass unanimously, so members held off on voting.

John Trumbull's painting, 'Declaration of Independence', depicting the five-man drafting committee of the Declaration of Independence presenting their work to the Congress. The original hangs in the US Capitol rotunda.

As delegates lobbied their home states to support the resolution, five men got to work on an accompanying document that laid out the reasons colonists wanted to sever ties with Britain. The Committee of Five, as it became known, was a political dream team: John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Roger Livingston. They nominated Jefferson to pen the first draft of what is now known as the Declaration of Independence.

In little more than two weeks, Jefferson churned out a draft that drew on a variety of other documents, including some of the up to 100 similar declarations that had been circulating in the buildup to the Lee Resolution. One, the Fairfax County Resolves, cowritten by George Washington and George Mason, claimed that the colonists’ constitutional rights had been violated by the British Parliament. Another, Mason’s 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights, affirmed that men had the right to “the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.”

Jefferson echoed that language in his draft document, which declared that “all men are created equal” and had an inalienable right to “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” He presented his draft to his fellow committee members and they made extensive edits before submitting it to the Continental Congress on June 28.

With the Declaration of Independence drafted, Congress was ready to debate Lee’s resolution for independence. But a test vote conducted on July 1 was anything but unanimous. Pennsylvania and South Carolina hoped there was still a chance to reconcile with Britain; they voted against independence. Delaware’s delegation was split. And New York abstained—its delegates were under orders not to impede a possible reconciliation.

The next day, on July 2, the delegates tried again. This time, the vote had a different outcome. Caesar Rodney, a Delaware delegate, had ridden through the night to Philadelphia, where he broke Delaware’s stalemate. South Carolina changed its position. And two of Pennsylvania’s delegates simply abstained from the vote, flipping their delegation in favor of independence. That day, the Congress voted unanimously for independence.

“The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America,” an ecstatic John Adams wrote to his wife Abigail the next day. “I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival...It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.”

But the document meant to accompany the resolution wasn’t quite ready. On July 3 and 4, Congress continued to discuss Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence. The most heated debate concerned a passage about slavery in which Jefferson accused King George III of violating the lives and liberty of “a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither.” In another passage, Jefferson accused the king of encouraging enslaved people to escape and join the English forces.

Although the debate was not documented, Jefferson later blamed South Carolina and Georgia for balking at the passage. But the entire Congress shared an economic interest in maintaining the institution of slavery: They knew that the colonies’ economy was largely based on the labor of enslaved people. Many delegates, including Jefferson himself, held slaves and personally profited from their labor.

Instead of laying the foundation for the abolition of slavery, the Congress deleted the controversial passage and combined the fleeting reference to slave revolts with another line from Jefferson’s draft that accused the king of encouraging Native Americans, whom they slurred as “savages,” to attack settlers at the British colonies’ western frontier.

With the Declaration of Independence complete, the Continental Congress voted to adopt it on July 4, 1776. It was received with great fanfare, and July 4—not July 2—is celebrated as the anniversary of American independence. The new republic’s independence would at last be secured with its Revolutionary War victory in 1783. But for those the document left out—enslaved people, Native Americans, and women—the celebrated declaration proved to be anything but a guarantee of equality.

---------oOo---------

Some pics:

A high-resolution image of the United States Declaration of Independence, this image being a version of the 1823 William Stone facsimile. Stone may well have used a wet pressing process (that removed ink from the original document onto a contact sheet for the purpose of making the engraving).

The flamboyance and size of the signature of John Hancock have made his name a synonym for signatures generally, as in “Put your John Hancock here.” Hancock proudly declared after signing: "There! I guess King George will be able to read that!"

The signed Declaration of Independence, now badly faded because of poor preservation practices during the 19th century, is on display at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

The opening of the Declaration's original printing on July 4, 1776, under Jefferson's supervision, was an engrossed copy made later with slightly differing lines between the two versions.

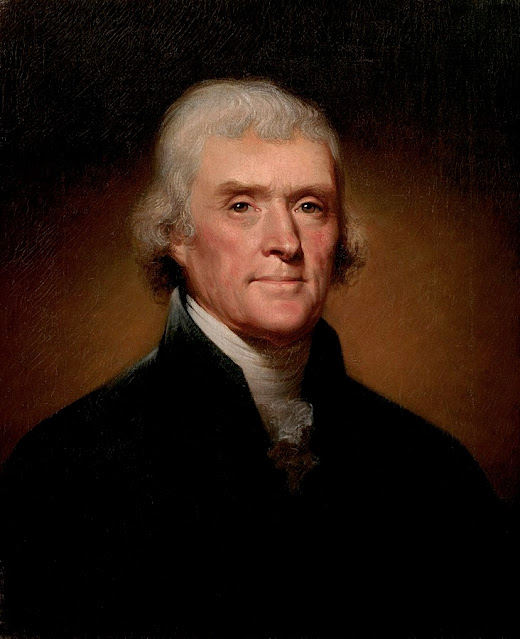

Thomas Jefferson, the principal author of the Declaration, depicted in an 1801 portrait by Rembrandt Peale

The Assembly Room in Independence Hall in Philadelphia, where the Second Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence

Writing the Declaration of Independence, 1776, a 1900 portrait by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris depicting Franklin, Adams, and Jefferson working on the Declaration

The portable writing desk on which Jefferson drafted the Declaration of Independence

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.