--------oOo-------

Continuing a look at the events and people in Billy Joel’s We Didn’t Start the Fire.

Each two lines represent a year.

Little Rock, Pasternak, Mickey Mantle, Kerouac

Sputnik, Chou En-Lai, "Bridge on the River Kwai"

Lebanon, Charles de Gaulle, California baseball

Starkweather homicide, children of thalidomide

Buddy Holly, "Ben Hur", space monkey, Mafia

Hula hoops, Castro, Edsel is a no-go

U-2, Syngman Rhee, payola and Kennedy

Chubby Checker, "Psycho", Belgians in the Congo

--------oOo-------

1959

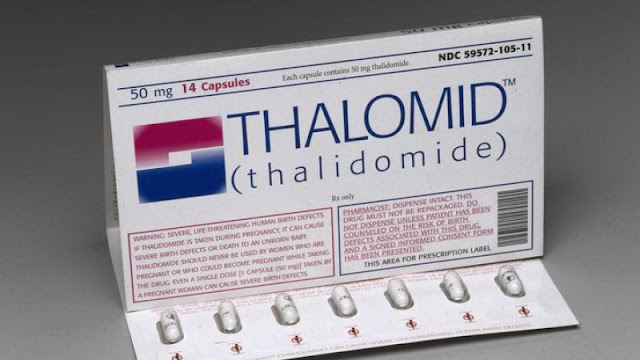

children of thalidomide

From:

The Science Museum

December 19, 2019

Thalidomide changed our relationship with new medicines forever. It took five years for the connection between thalidomide taken by pregnant women and the impact on their children to be made. Not only did thalidomide change people’s lives, but it resulted in tighter drug testing and reporting of side-effects.

Thalidomide in the marketplace:

Thalidomide is a drug that was developed in the 1950s by the West German pharmaceutical company Chemie Grünenthal GmbH. It was originally intended as a sedative or tranquiliser, but was soon used for treating a wide range of other conditions, including colds, flu, nausea and morning sickness in pregnant women.

During early testing, researchers at the company found that it was virtually impossible to give test animals a lethal dose of the drug. Largely based on this, the drug was deemed to be harmless to humans. Thalidomide was licensed in July 1956 for over-the-counter sale (no doctor’s prescription was needed) in Germany.

Around the world, more and more pharmaceutical companies started to produce and market the drug under license from Chemie Grünenthal. By the mid-1950s, 14 pharmaceutical companies were marketing thalidomide in 46 countries under at least 37 different trade names.

In 1958, thalidomide was produced in the United Kingdom by The Distillers Company (Biochemicals) Ltd, under the brand names Distaval, Tensival, Valgraine and Asmaval. Their advertisement claimed that

“Distaval can be given with complete safety to pregnant women and nursing mothers without adverse effect on mother or child.”

The drug was prescribed for a range of conditions including pneumonia, colds and flu and for relieving the symptom of nausea often experienced in early pregnancy.

One country that did not approve thalidomide for marketing and distribution was the USA, where it was rejected by the Food and Drug Administration. Pharmacologist Frances Oldham Kelsey turned down several requests from the distributing company who did not provided clinical evidence to refute reports of patients who developed nerve damage in their limbs after long-term thalidomide use. This prevented the drug thalidomide from ever being used in the United States.

Thalidomide and Pregnancy:

In the 1950s, scientists did not know that the effects of a drug could be passed through the placental barrier and harm a foetus in the womb, so the use of medications during pregnancy was not strictly controlled. And in the case of thalidomide, no tests were done involving pregnant women.

As the drug was traded under so many different names in 49 countries, it took five years for the connection between thalidomide taken by pregnant women and the impact on their children to be made. A UK Government warning was not issued until May 1962.

One reason why researchers and doctors were slow to make this connection was due to the wide range of changes to foetal development. Limbs, internal organs including the brain, eyesight and hearing could all be affected.

Later, they found that the impact on development was linked to when during pregnancy the drug was taken, and effects only occurred between 20 and 37 days after conception. After that, thalidomide had no effect on the foetus.

Another reason why it took so long to establish the link to thalidomide was that some of the damage caused by the drug was very similar to certain genetic conditions that affect the upper or lower limbs.

Thalidomide Scandal:

The first time the link between thalidomide and its impact on development was made public was in a letter published in The Lancet from an Australian doctor William McBride, in 1961.

The drug was formally withdrawn by Chemie Grünenthal on 26 November 1961 and a few days later, on 2 December 1961, the UK distributors followed suit. However, it remained in many medicine cabinets under many different names.

In the few short years that thalidomide was available, it's estimated that over 10,000 babies were affected by the drug worldwide. Around half died within months of being born. The thalidomide babies who survived and their families live with the effects of the drug.

The Thalidomide Society was formed in 1962 by the parents of children affected by the drug thalidomide. The original aim of the Society was to provide mutual support and a social network as well as to seek compensation.

In 1968 Chemie Grünenthal was brought to trial in Germany. The company settled the case out of court and arrangements were made to compensate German victims. No one was found guilty of any crimes.

The same year, the British licensee, the Distillers Company, also reached a compensation settlement with the UK victims of the drug. In the UK, payments from Distillers, as well as government compensation, were administered by the Thalidomide Trust.

In 1972, a highly publicised campaign led by the Sunday Times newspaper helped to secure a further settlement for children affected by thalidomide in the UK.

The Consequences of Thalidomide

Thalidomide forced governments and medical authorities to review their pharmaceutical licencing policies. As a result, changes were made to the way drugs were marketed, tested and approved both in the UK and across the world.

One key change was that drugs intended for human use could no longer be approved purely on the basis of animal testing. And drug trials for substances marketed to pregnant women also had to provide evidence that they were safe for use in pregnancy.

The easy, over-the-counter access to thalidomide prompted many countries to improve their classification and control of medicines. In the UK the 1968 Medicines Act, passed as a result of the thalidomide scandal, made distinctions between prescription drugs, drugs only available in pharmacies and drugs available for general sale.

The Yellow Card Scheme was set up for doctors to share previously unknown side effects of medications they prescribed. The Scheme has now widened so anyone can report a side effect.

In the UK thalidomide is only prescribed by a doctor under strict controls. Women taking thalidomide are required to use two forms of birth control and regular pregnancy tests. Men are required to use contraception when taking thalidomide. People who are prescribed thalidomide undergo counselling and are talked through the risks.

Use of Thalidomide today:

This was not the end of the thalidomide story. In 1964 a leprosy patient at Jerusalem’s Hadassah University Hospital was given thalidomide when other tranquilisers and painkillers could not help him. His doctor, Jacob Sheskin, noticed the drug had an effect on the patient’s leprosy symptoms.

Within three days the leprosy had gone and skin lesions healed. When the patient stopped taking the thalidomide the leprosy returned. The drug seemed to be able to suppress the disease, although it was not a cure.

As a result, the World Health Organisation (WHO) ran a clinical trial on the use of thalidomide for leprosy in 1967. And after more positive results, thalidomide was used as a treatment for leprosy in many countries.

More recently, it has been used successfully to control some AIDS-related conditions, and as a targeted cancer drug for treating cancers such as multiple myeloma.

But the renewed use of thalidomide remains controversial because of its past history.

--------oOo-------

Some additional items:

Thalidomide and Australia:

Worldwide, more than 10,000 children are estimated to have been born with birth defects because of thalidomide use, with an estimated 40% of these children dying within a year- external site. Thalidomide survivors continue to live with the impacts of the drug today.

At the time, Australia did not have a system for evaluating the safety of medicines before they were permitted on the market. Although thalidomide was ultimately removed from the market, this was only after many pregnant women in Australia had already taken the medicine.

The thalidomide tragedy demonstrated to Australians that medicines and other therapeutic goods need to be evaluated for safety and efficacy (that the medicine does what it says it will). A series of regulatory changes culminated in the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989, which established the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) as Australia’s national regulator of medicines and medical devices.

In 2014 a judge formally approved an $89 million settlement for Australians and New Zealanders living with severe physical deformities because their mothers used the controversial drug thalidomide during pregnancy.

Supreme Court Justice David Beach described the settlement as ‘‘more than fair’’.

Dr William McBride:

Dr William McBride (1927 – 2018) published a letter in The Lancet, in December 1961, noting a large number of birth defects in children of patients who were prescribed thalidomide, after a midwife named Sister Pat Sparrow first suspected the drug was causing birth defects in the babies of patients under his care at Crown Street Women's Hospital in Sydney.

McBride was awarded a medal and prize money by L'Institut de la Vie, a prestigious French institute, in connection with his discovery, in 1971. Using the prize money, he established Foundation 41, a Sydney-based medical research foundation concerned with the causes of birth defects. Working with P H Huang, he proposed that thalidomide caused malformations by interacting with the DNA of the dividing embryonic cells. This finding stimulated their experimentation, which showed that thalidomide may inhibit cell division in rapidly dividing cells of malignant tumours. This work was published in the journal "Pharmacology and Toxicology" in 1999 and has been rated in the top ten of the most important Australian medical discoveries

McBride's involvement in the Debendox case is less illustrious. In 1981, he published a paper indicating that the drug Debendox (marketed in the US as Bendectin) caused birth defects. His co-authors noted that the published paper contained manipulated data and protested but their voices went unheard. Multiple lawsuits were filed by patients, and McBride was a willing witness for the claimants. Eventually, the case was investigated and, as a result, McBride was struck off the Australian medical register in 1993 for deliberately falsifying data. An inquiry determined "we are forced to conclude that McBride did publish statements which he either knew were untrue or which he did not genuinely believe to be true, and in that respect was guilty of scientific fraud." He was reinstated to the medical register in 1998.

Relevance to 1959:

Thalidomide went on the market in 1957. Doctors initially observed nerve damage in adults, followed by an increase in deformities in children from 1959 onward. The cases became increasingly frequent.

-----------oOo---------

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.